How To Get International Keyboard On Iphone

Today, multitouch keyboards are commonplace, enabling users to tap out texts with increasingly rapid speed on iPhones and Androids. But it's important to remember that just six years ago, in the age of BlackBerry and Nokia, physical keyboards were the only solution in the mobile world–one huge hurdle Apple needed to overcome in order to make its new smartphone a success. And to work out all the kinks and bugs, the main force driving Apple's engineers–of all things–was The Simpsons.

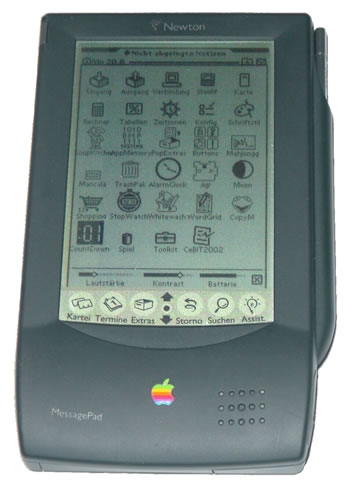

The insight comes as part of Fast Company's recent oral history of design at Apple, comprised of interviews with dozens of insiders and past executives. According to a former high-level engineer, one of the top priorities for Scott Forstall, then-senior vice president of iOS software at Apple, was to nail the keyboard. He knew if he couldn't deliver on the promise of typing, then multitouch, the core method for interaction on the iPhone, would be a failure. Critics, infamously including Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, were loudly proclaiming that the iPhone would be a flop, even before it hit market, because the device lacked a physical keyboard. "Scott was very focused on the keyboard," recalls Nitin Ganatra, Apple's former director of engineering for iOS applications. "Everybody on the team knew full well that Apple had attempted to ship a device in the past with an alternative touch-form input, and it was laughed at by the industry: the Apple Newton."

To make the point clear of how much the device was laughed at, Forstall turned to The Simpsons, the beloved animated series. In 1994, during the sixth season of the show, The Simpsons lambasted the recently released Newton, which was then notorious for over promising and under delivering on performance, especially regarding its handwriting recognition. In one scene of the episode, Kearney and Dolph, two bullies on the show, decided to take a memo. "One of the characters picked up a Newton and writes, 'Beat Up Martin,' and it was translated as, 'Eat Up Martha,'" Ganatra explains. Disappointed at the result, Kearney then chucks the Newton at Martin's head–about the only task the early tablet was good for.

"In the hallways [at Apple] and while we were talking about the keyboard, you would always hear the words 'Eat Up Martha,'" Ganatra recalls. "If you heard people talking and they used the words 'Eat Up Martha,' it was basically a reference to the fact that we needed to nail the keyboard. We needed to make sure the text input works on this thing, otherwise, 'Here comes the Eat Up Marthas.'"

At one point during the troubled development, Apple decided to hold a weeklong hackathon to get the keyboard project back on its feet. "We let all the engineers on Monday morning work on alternate versions of the keyboard: Maybe people will come up with something even better than the core layout we see today," Ganatra says. "It was understood that the contact points that you make with the keyboard are far smaller than the physical size of your thumb, so, 'Holy shit, what are we going to do about it?'"

The team had already entertained novel ideas for improving performance, including the idea of auto-correct. The hackathon birthed wilder concepts. "Some of the crazier ideas included a larger virtual keyboard that would slide back and forth as you got closer to one end or the other," says Ganatra, who is now an executive director at Jawbone. "The keyboard itself–let's say it's 320 pixels across–would actually be 500 pixels and would shift back and forth based on what you needed to type. There were also some keyboards that were developed to be used with multiple taps. It was a version of the multi-task keyboards you see now."

The ideas, while promising, never made it into the final product. The reason? As Ganatra says, "At that time, there was still that big concern of the 'Eat Up Marthas.'"

A team of Fast Company reporters spent months interviewing more than 50 former Apple execs and insiders, many of whom had never spoken publicly about their work. Read part four of the oral history here, which covers the creation of the iPhone. An extended version of this oral history is available from Byliner. Purchase it here.

How To Get International Keyboard On Iphone

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3017039/how-the-simpsons-fixed-apples-iphone-keyboard

Posted by: hawkinsthatted.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Get International Keyboard On Iphone"

Post a Comment